I was searching for something else when monitoring the Research Room at the Dales Countryside Museum earlier this year. That search led me to the 1895 copies of the Hawes Parish Magazines. And, as often happens, I became fascinated by something totally different having spotted the line drawings and short explanations about the Street Criers of London. I’m very grateful to Hawes Parochial Church Council for letting me reproduce them.

The text and pictures in the magazines were not accredited nor did the author provide a date for the artwork. The text below is the same as in the magazines. Where the text was incorrect I have provided updated explanations in brackets and in italics.

Street folk and cries of old London

It is curious to observe the changes which come over the manners and customs, the dress and speech, of civilised nations. These changes are so gradual that we do not notice them at the time, though those who are old sometimes are startled when they realise how different things are from what they were in their youth. The changes are still more marked when we go back to a former generation. It will interest our readers to see from an old book of illustrations, what some of the street folk of London were like long ago, and to learn some of the cries with which they plied their humble trades.

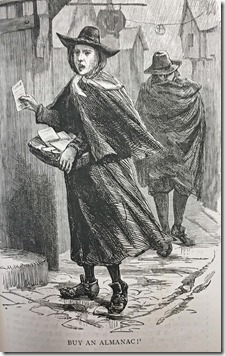

Almanac seller

Early almanacs were called ‘prognostications’ because they dealt with astrology, professing to learn from the stars what were favourable seasons. They foretold battles, pestilences, famines, and the like. Almanacs have now grown to be such marvellous shilling volumes as Whitaker’s – full of various information from all parts of the world. But the pamphlet which was hawked in the street a hundred years ago contained very little information, if we may accept a rhyme which was then in vogue: –

Early almanacs were called ‘prognostications’ because they dealt with astrology, professing to learn from the stars what were favourable seasons. They foretold battles, pestilences, famines, and the like. Almanacs have now grown to be such marvellous shilling volumes as Whitaker’s – full of various information from all parts of the world. But the pamphlet which was hawked in the street a hundred years ago contained very little information, if we may accept a rhyme which was then in vogue: –

‘My almanacs aim at no learning at all,

But only to show when the holidays fall;

And tell, as by study we easily may,

How many eclipses the year will display.’

[The first edition of Old Moore’s Almanack was published in 1697 and published weather forecasts. From 1700 it contained astrological observations and became a best seller in the 18th and 19th centuries – Wikipedia.]

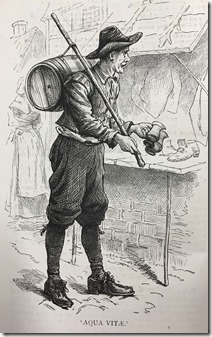

Aqua Vitae

Before the days of licensed houses, the travelling liquor-seller frequented the streets with his keg on his back, and his cry, Aqua Vitae (water of life), a sad misnomer for his fiery spirit. In our day the exciseman and the policeman would be soon on his track, and would silence his cry.

Before the days of licensed houses, the travelling liquor-seller frequented the streets with his keg on his back, and his cry, Aqua Vitae (water of life), a sad misnomer for his fiery spirit. In our day the exciseman and the policeman would be soon on his track, and would silence his cry.

In the interests of sobriety we would be ready to have him back if we could get rid of the glaring gin-shops which have taken his trade from him; but if we must have these ruinous public-houses at every corner, we may be thankful that the street folk of today tempt the passer-by only with ice-creams and lemon-squash instead of with the beer and brandy of long ago.

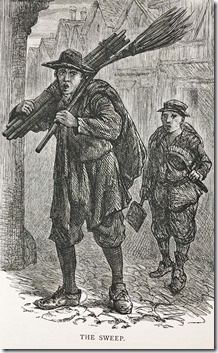

Sweep, Ho!

In old times the trade of a chimney sweep was a harder one than it is now. Boys used to be sent up the chimneys with a short brush to knock the soot off the sides of the flue. These boys had to be small and thin, as the chimneys were often very narrow and crooked.

In old times the trade of a chimney sweep was a harder one than it is now. Boys used to be sent up the chimneys with a short brush to knock the soot off the sides of the flue. These boys had to be small and thin, as the chimneys were often very narrow and crooked.

Boys used to be forced up by their cruel masters, and even fires lighted at their feet that they might make frantic efforts to push upwards.

Many stories were told of the sufferings of these boys. Sometimes they stuck fast, and could neither get up nor down, and the chimney had to be broken open to remove the body of a suffocated climbing-boy.

[A sweeping machine was invented in the early 19th century. The Act of Parliament in 1875 finally put a stop to using children to sweep chimneys.]

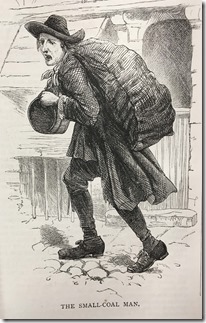

Small Coal

We do not nowadays see the coalman with his sack on his back and his measure in his hand. When coals are hawked about the streets it is in a wagon, and the law takes care that good measure is given.

We do not nowadays see the coalman with his sack on his back and his measure in his hand. When coals are hawked about the streets it is in a wagon, and the law takes care that good measure is given.

In 1670 there used to be seen in the London streets a remarkable man like the dealer in the picture, who cried out as he went along, ‘Small coal for sale!’ in so musical a voice that he attracted all who passed by. His name was Thomas Britton and he had a coal shed with a small house beside it in Clerkenwell.

He was a lover of learning and a skilled musician. Here, when the day’s work was done, he used to assemble his friends, and by degrees his concerts in his little room became so famous that even such a celebrity as Handel was found there.

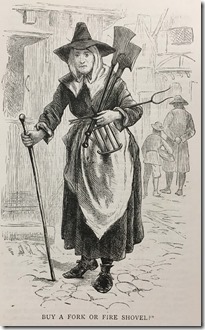

Buy a Fork or Fire Shovel?

The little gridiron and shovel in our picture do not need any remark, but the fork is not a household implement of our day.

The little gridiron and shovel in our picture do not need any remark, but the fork is not a household implement of our day.

It was probably used for lifting the rushes which were spread on the floor by our ancestors in place of carpets.

It is said that it was the custom to fork over these rushes and remove those which had become sodden, and to spread a layer of fresh ones on the top. If that were so, we cannot wonder at the plagues and sicknesses which were common in those times.

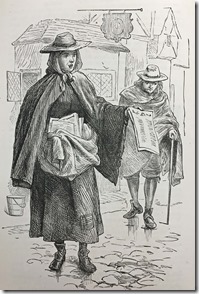

‘London Gazette’ here!

The origin of our English newspaper was in 1588 when the people were in alarm at hearing of the advance of the Spanish Armada, the great fleet which was to conquest the country, and the paper was published by the authority to allay public fears.

The origin of our English newspaper was in 1588 when the people were in alarm at hearing of the advance of the Spanish Armada, the great fleet which was to conquest the country, and the paper was published by the authority to allay public fears.

The London Gazette [was first published in 1665] and belongs to the Government. A complete set of this newspaper consists of more than 400 volumes and four volumes of index.

The sheet which the girl in the picture is offering for sale is much less bulky than the Gazette of the present day, but it contained more exciting reading. In those war-times her cry used sometimes to be:

‘In the Gazette great news to-day,

The enemy is beat, they say.’

Milk here

The sellers of water no longer tramp along London streets but the milkman or the milkmaid still are seen and heard. The old cry used to be ‘Any milk here’, and sometimes the words were added, ‘Fresh cheese and cream’. A little later the cry was, ‘Milk here, maids, below’, then ‘Milk below’, and thus by degrees the cry contracted into ‘Mee-on’ which is what we hear.

The sellers of water no longer tramp along London streets but the milkman or the milkmaid still are seen and heard. The old cry used to be ‘Any milk here’, and sometimes the words were added, ‘Fresh cheese and cream’. A little later the cry was, ‘Milk here, maids, below’, then ‘Milk below’, and thus by degrees the cry contracted into ‘Mee-on’ which is what we hear.

In the days when such milkmaids as our picture show traversed London streets, there were cows in the fields about St Martin’s Church and Hatton Garden. ‘Merrie Islington’ was then a village to which folk went for milk warm from the cow, and to enjoy cream and cakes under the pleasant trees.

Now the milk of London comes up from the distant country in tin churns. At the railway station hundreds of these great cans arrive by the ‘milk trains’. Men with vans and carts are waiting to carry them off to the dairies, from which the milk-lads and milk-maids go round to the customers.

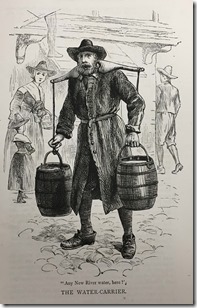

New River Water

The way in which London of today is supplied with water would have surprised the folk of long ago as much as the way in which it is supplied with milk. The London of those days had only conduits, or wells, here and there. It is said that water first flowed from a conduit in West Cheap in [the late 13th century], bought thither from Tyburn through leaden pipes which took fifty years to lay down. Baynard’s Water, now Bayswater, had ten conduits. At these men filled their pails and then carried the water along the roads, selling it as much a quart, which they measured with a tankard. Hence, in James the First’s time, the water-carrier was called a ‘tankard-bearer’. Ben Jonson, in 1568, in Every Man in his Humour, makes Cof, the water-bearer say, ‘I dwell, sir, at the sign of the Water Tankard.’

The way in which London of today is supplied with water would have surprised the folk of long ago as much as the way in which it is supplied with milk. The London of those days had only conduits, or wells, here and there. It is said that water first flowed from a conduit in West Cheap in [the late 13th century], bought thither from Tyburn through leaden pipes which took fifty years to lay down. Baynard’s Water, now Bayswater, had ten conduits. At these men filled their pails and then carried the water along the roads, selling it as much a quart, which they measured with a tankard. Hence, in James the First’s time, the water-carrier was called a ‘tankard-bearer’. Ben Jonson, in 1568, in Every Man in his Humour, makes Cof, the water-bearer say, ‘I dwell, sir, at the sign of the Water Tankard.’

[Sir Hugh Myddleton master-minded the ‘New River’ from Amwell and Chadwell in Hertfordshire which was constructed between 1608 to 1613 to bring fresh water to London. Water was also piped in, using wooden pipes, from natural springs via Islington.]

There was a great dislike at first to water conveyed in pipes, so that we find a water-carrier having for his cry, ‘Any fresh and fair spring water here? None of your pipe sludge’. But the New River water won its way to favour and in the ‘Islington Garland’ a rhyme of the period, we read:

‘Joy to thy spirit, aquatic Sir Hugh,

To the end of old time shall thy river be new.’

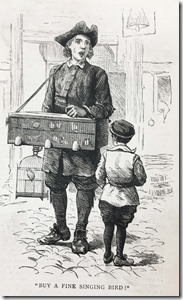

The bird-seller

Londoners are still fond of having singing birds in cages but we have not a street hawker of them like the man in the picture. In the working folk’s markets you may sometimes see a truck with an array of small wooden cages, each holding a bird, but the trade is done chiefly in shops.

Londoners are still fond of having singing birds in cages but we have not a street hawker of them like the man in the picture. In the working folk’s markets you may sometimes see a truck with an array of small wooden cages, each holding a bird, but the trade is done chiefly in shops.

The singing birds are some of the wild birds which have been caught, and some of the canaries which have never known freedom. We can look with pleasure on the canaries for they have always lived in cages and if they were set free they would die, either from not knowing how to find food, or from being pecked by sparrows and other wild birds.

Many working men are skilful in breeding canaries and there are various fancy kinds which are much valued. But wild birds, which should be the feathered songsters of the grove, but which have been caught and imprisoned in small cages, are a sad sight. It is not uncommon to see a lark in a tiny cage, with a bit of turf in the bottom, fastened outside a window and to hear it pouring out its thrilling notes as if it were soaring up into the sky. One wonders how any one can find pleasure in listening to the poor little captive.

The bullfinch is a favourite cage-bird; but they are becoming scarce in England, and the noted ‘piping’ bullfinches come from Germany. The goldfinch, too, is a popular cage-bird and, it is said, that as many as 70,000 have been caught in one year in England.

Bird-catchers use decoy birds which are allowed to flutter up from the cage to which their leg is tied to attract wild birds to the net. They also use a small mouth instrument named a ‘bird-call’. This is referred to by Chaucer: ‘So the birde is begyled with the merry noise of the fowler’s whistle, when it is closed in the nette.’

Mr Mayhew tells of a famous old bird-catcher of about eighty years ago, and he gives some of old Gilham’s experiences in his own words: ‘I’ve caught goldfinches in lots at Chalk Farm, and all along where there’s that railway smoke and noise by Primrose Hill. I’ve catched them where there’s all them big squares Pimlico way. I don’t know what the bird trade will come to. It’s hard for a poor man to have to go all the way to Finchley for birds that he could have catched at Holloway; but people never thinks about that. Ah, well! What’s it all coming to?’

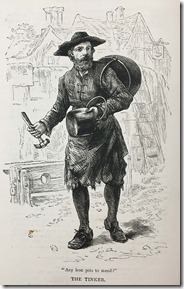

Any Iron Pots to Mend?

‘Any brass pots or iron pots to men?’ was the cry of the tinker of a hundred years ago. Like most of the wandering traders, he did not hold with the proverb ‘Self praise is no commendation’ for he used to shout:

‘Any brass pots or iron pots to men?’ was the cry of the tinker of a hundred years ago. Like most of the wandering traders, he did not hold with the proverb ‘Self praise is no commendation’ for he used to shout:

‘Your coppers, kettles, pots, and stew-pans,

Though old shall serve instead of new pans;

I’m very moderate in my charge

For mending small as well as large.’

The trade of the tinker is made interesting by the fact that John Bunyan, the famous author of the Pilgrim’s Progress, earned his living in this way, and paraded the streets of Bedford saying, as he want, ‘Mistress, have you work for the tinker? Pots, pans, kettles I mend; old brass, lead, or old copper I buy. Anything in my way today maids?’

In the picture, behind the tinker, we see those bugbears of unruly villagers, the parish stocks. Has the artist of the day put them there as a sly hint that they were old friends of ‘the jolly tinker’? It certainly was held in those times that he often deserved to be put in them for his dishonest doings.

Ripe Strawberries

Our readers who have seen the great street in London called Holborn, with its pavements crowded with passengers and its roadway with omnibuses and waggons, would hardly think that there were every strawberry gardens there. Yet a few paces from Holborn there still is a street called Ely Place where, long ago, was the town house of the Bishops of Ely, and its garden was famous for strawberries.

Our readers who have seen the great street in London called Holborn, with its pavements crowded with passengers and its roadway with omnibuses and waggons, would hardly think that there were every strawberry gardens there. Yet a few paces from Holborn there still is a street called Ely Place where, long ago, was the town house of the Bishops of Ely, and its garden was famous for strawberries.

Shakespeare, in his Richard III, makes the Duke of Gloucester say, ‘My Lord of Ely, when I was last at Holborn I saw good strawberries in your garden there. I do beseech you send me some of them.’

‘Ripe Strawberries’ is still a cry of the London streets, though it generally comes from a man with a truck or wheelbarrow. The hawkers of our day sell their strawberries in little round baskets made of wood shavings. The girl in the picture has the shape of basket used till some twenty years ago, and was called a ‘pottle’. It often had fine berries at the top and poor ones at the bottom, the shape lending itself to cheating. This explains the following old cry – ‘hautboys’ was the name of the fine kind of strawberry: ‘Rare ripe strawberries. Hautboys sixpence a pottle; full to the bottom – hautboys.’ [from Hautbois – musk strawberries] Another specimen of an old cry in rhyme was this:

‘Ripe strawberries, a full pottle for a groat,

They are all ripe and fresh gathered, as you see;

No finer for money I believe can be bought,

So I pray you come and deal fairly with me.’