“I was impressed by her enthusiasm to take on any challenge and travel to any location in order to serve the Lord she loved,” wrote Russell Board, one of the directors of World Mission Ministries, about Joy Bausum following her death in Malaysia on August 18 2010, aged 26. That could certainly have been written about Joy’s great, great, great grandmother Jemima. Her career in the 19th century began in south Kalimantan (Borneo) after the long voyage around Africa and took her via Penang to Ningbo in China. It started when the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East (SPFEE) received an application from “Miss Poppy school mistress from Maidenhead”. It ended with her playing a very important role in the lives of James and Maria Hudson Taylor and the founding of the China Inland Mission .

Maidenhead to Borneo

Jemima was free to make her own decisions about where she lived and worked because her father, Jonathan Poppy, had died in January 1838, 29 days before her 20th birthday. His will was not probated in Norfolk until November 1843 so it was likely that Jemima did not receive any of her inheritance until then.

She found a teaching post at Maidenhead and may have arrived in that busy brewery town in time to see the first train cross Isambard Brunel’s magnificent bridge. Many had prophesied that the bridge, which crossed the River Thames in two great strides, each span being 128 ft (39m) wide, would collapse when the wooden props were taken away! It still stands today like a memorial to how visionary ideas can be successfully accomplished. But could a young, single woman in the 19th century fulfil a visionary calling?

Jemima would have been aware that the SPFEE had made it possible for some to do so. By the end of 1838 the London committee had sent 13 women overseas. One of the first was the Englishwoman, Eliza Thornton, who successfully set up girls’ schools in Jakarta (then Batavia) after arriving there in 1835.

In the society’s records no reason was given for the delay between receiving Jemima’s application and her beginning the mandatory probation period in May 1842. It is likely, however, that between 1839 and 1842 she not only continued working as school teacher but had also built a strong relationship with a church for she needed good testimonials from both to be accepted by the SPFEE. Her referees had to assure the society that she had given evidence of real piety, and had maintained a temper and deportment consistent with her Christian character and profession. They were asked if she also “embraced opportunities for usefulness” by benefitting others such as by teaching at a Sunday School or visiting the sick. The society wanted to be sure she was a good communicator; had good sense, judgement and prudence; was mild, courteous and humble; and evinced patience and perseverance.

Jemima had to convince the women who interviewed her that she had sound protestant doctrines and that she had the right reasons for wanting to be a missionary, besides showing that she was well equipped as a teacher. Following a successful interview Jemima began a period of probation at a British and Foreign School Society institution in London.

The SPFEE was careful to find a ship which was suitable for her as a single women to travel on, and (as with all their agents) would bring her home in the case of sickness or any unlooked-for emergency. But, like many mission agencies at that time, the SPFEE did not even think it necessary to prepare their candidates for living in a very different culture. Nor did the society research the location to which it decided to send Jemima.

All it had was a letter of invitation from a Swiss woman who had gone to work with Miss Thornton in 1838. Emma Cecilia Combe from Berne had initially been accepted by the Geneva Auxiliary Committee. After Ms Combe married an American missionary, the Rev Frederick B Thomson,in December 1840 she continued superintending a girls’ school in Jakarta. But in February 1842 the Dutch colonial government insisted that she and her husband should join the American missionaries in southern Kalimantan. They moved to a compound deep in the forest – and it was from there that Mrs Thomson wrote to the SPFEE. Her life and death in Kalimantan would greatly affect Jemima.

Back in England Jemima must have wondered if she would ever begin what she saw as being her life’s work. After successfully completing her probationary period in early 1941 the SPFEE finally found a ship captained by a man it could trust to take care of single women. But then he died – and they had to search for another vessel. It wasn’t until March 1843 that Jemima sailed from Gravesend little realising that it would be over a year before she reached her destination.

By early 1844 she was in Singapore and wondering how she could get to the American mission base in Pontianak for the seas around Kalimantan were infested with pirates.

The problem was solved when she managed to hitch a lift with James Brooke who had just become the white rajah of Sarawak. His adventures would inspire the term Sarawaking which stood for white adventurism that turned ordinary men into kings of far away domains. He was one of those upon which Kipling based his book The Man who would become King. George McDonald also drew on Brooke’s life for his Fraser Flashman books. Jemima’s story was equally as amazing.

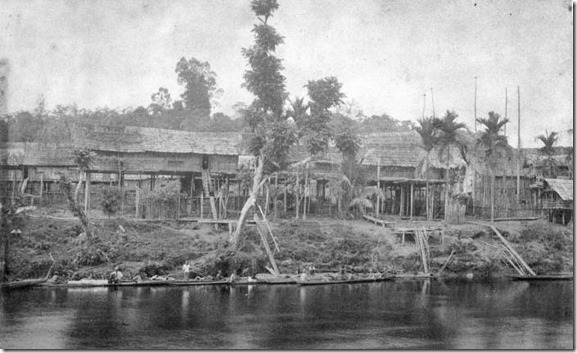

Brooke would certainly have told her about the head hunting Dayaks who lived in Kalimantan. Yet from Pontianak she faced a four to five day journey by canoe deep into the forest. Below – the type of Dayak longhouses Jemima would have seen. Photo taken in 1894 on the Kahayan River, now with Tropenmuseum, part of the National Museum of World Cultures, via Wikimedia Commons.

Today tourist agencies organise adventure holidays into that area offering the great jungle experience, braving rapids, staying overnight in Dayak longhouses and meeting the tattooed descendants of the headhunters. At the end there is a comfortable hotel with all mod-cons and the internet on which to share experiences. Back in the 1840s it could take up to six months for mail from the States to reach Pontianak.

So, although Mrs Thomson had requested the SPFEE to send an agent, she had no idea that anyone had been sent. “No previous advice of her coming had reached me; she had landed quite unexpectedly at our far-distant missionary premises in the wilderness of Borneo,” she wrote to the SPFEE after Jemima arrived.

It had been in the autumn of 1842 that her husband and the Rev William Youngblood had chosen a site by the river ten minutes walk from Karangan, having already gained the permission of the local Malay ruler at Pontianak. As it was difficult to find local labourers to help clear the almost impenetrable forest the Americans had to do most of the work themselves, clearing a 24 acre site so they could have a large vegetable garden and orchard as well as space for the mission buildings. It was tough work for, with Pontianak on the equator, there was no escape from the heat or the myriads of mosquitoes.

The two bamboo and wood houses they built were raised up on posts to help keep them dry and free from snakes and other wild life. The roofs were covered with broad leaves and slabs of bark. Thomson brought his wife and children to Karangan in early 1843.Within two years the land they had cleared had groves of plantains, coffee, fruit trees, spice trees, and pineapples. The latter were grown beside the houses because their thorns kept out rodents and other animals.

The wild and often pathless forest around them provided cover for porcupines, wild cats, scorpions and centipedes. So it was very difficult for the ladies to visit their neighbours. Nor did they find it easy to understand the Dayaks. The missionaries could not comprehend their unwillingness to learn to read, how they lived together in large groups, or their animistic beliefs.

Seven months after her arrival Jemima wrote: “Our prospects are very dark at this time. The people at the nearest kampong (longhouse) avoid coming near us, unless it is to steal or to beg, or in hope of some sordid gain: they seem entirely to refuse instruction, and try to perplex us in every way they can, yet, we hope not from a spirit of malice or hatred, but because they like to show their importance, or to show how far they dare go in deeds of darkness. They seem to feel a savage pleasure in thinking themselves able to perplex a white man.”

There was certainly much to perplex the missionaries. Not only did the Dayaks have no written language but there were several dialects within a small area. There was no big centre of population but rather 3,000 people scattered in 15 villages within a day’s walk. Mr Thomson and Mr Youngblood often got lost on the poorly marked trails and had to wade through swamps.

When they reached a longhouse the Dayaks would usually share their scarce food supplies with their visitors such as rice, eggs, pumpkins, cucumbers and cocoa water. But they had to eat these surrounded by smoked human heads which the Americans found revolting. The Americans, however, noted that the custom of head hunting seemed to be in decline in that area and that the Dayaks there were peace-loving, inoffensive and docile. The Dayaks loved a good story and when everyone gathered in the longhouse in the evening they especially enjoyed those about the Creation and the Flood, and the doctrine that all (including Dayaks) were equal before God.

By 1844, however, the American mission at Karangan was struggling to survive. Mr Youngblood moved his family to Pontianak as his wife was not well and a single man joined those at Karangan. Then came the fatal blow when in December 1844 Mrs Thomson died. The men at Karangan reported later: “One whom we were disposed to regard as all-important to our comfort and efficiency, has been taken from the midst of us… Since her decease, every feasible attempt has been made to attain the same end, but all has proved unavailing. A family circle is a sanctuary, which a missionary to such people needs above every other external comfort.”

Mrs Thomson’s presence had safeguarded them from suspicion and much more. The Dayak women now expected sexual favours from them, something the missionaries found unthinkable and embarrassing. Lady Sylvia Brooke, Ranee of Sarawak (1885-1971) wrote: “The Dayaks ravish my senses, the boys as much as the young girls, who, with uplifted breasts, were simple and unashamed, and had delicate swift movements like little wild fauns.”

By the time he left Karangan Mr Thomson had buried two daughters and a son in the little cemetery there. Emma Thomson was buried at Pontianak where she had died. With two daughters left, one by each of his wives, Mr Thomson headed West. At St Helena he sent his oldest daughter on to America to her maternal grandparents in New Brunswick, New Jersey. He travelled with his youngest daughter via Marseille to Berne, where he died in March 1848.

By 1845 Jemima had realised that her hope of living and dying among the Dayaks had come to an end. She told the SPFEE: “Oh what a brittle thread do all our earthly hopes hang! Blessed indeed shall we be if we learn, by all the Lord’s dealings with us, to hold our souls in readiness for whatever He may send, so that, whether he fulfils our desires, or blight our hopes, we may bow with perfect submission, and, with his servant of old, say, ‘Though he slay me, yet will I trust him.’”

She heard about the need for a school superintendent in Penang and moved on.

Penang, Maria Dyer and Johann George Bausum

In Penang in 1845 Jemima had the opportunity to learn from a woman who proved to be one of the most successful at setting up schools for Chinese girls. Maria Dyer founded the Chinese Girls’ School in Singapore in 1842. That has become St Margaret’s Primary and Secondary Schools and is very proud of being the oldest girls’ school in Singapore and the Far East.

Maria handed over the school to the SPFEE agent, Miss Grant, in mid 1843 and then suffered the double tragedy of losing both a baby son and her husband, Samuel. He was an exceptional linguist and printer who had developed a quicker way of printing texts in Chinese. Samuel died immediately after attending a conference in Hong Kong where the western missionaries decided which of the five newly-opened treaty ports in China they would work in following the British victory in the 1st Opium War.

This was the move that the Dyers had so longed for – but as a widow with three children Maria decided instead to return to Penang especially as so many missionaries were moving to China. Her youngest daughter (who became the first wife of J Hudson Taylor, the founder of the China Inland Mission) commented later that her mother felt she should be in Penang as there were no missionaries there by then and she could reach men and women equally. That was a revolutionary stance as the mission societies believed that women should only work with women and girls.

The Dyers had obviously done a lot of preparation for their career on the mission field. Samuel was one of the men who attended the Chinese language classes run by Robert Morrison between 1824 to 1826. When Robert Morrison reached China in 1807 he experienced tremendous difficulty in learning the language because the Chinese government forbade anyone – with the penalty of death – to teach it to foreign barbarians. So when he was back in England in he was determined to share what he had learnt. He was very keen to recruit single women for the work among the Chinese and had a language class for three to four ladies, including Maria. Maria’s father, Joseph Tarn, was a director of the LMS, so she had probably grown up in a household full of mission stories.

She certainly had heard that “fancy goods” as the SPFEE came to call them were a very useful way of raising funds to cover the cost of setting up non-fee paying girls’ schools for she carried a lot of them with her when, with her husband, she sailed to Penang in 1827. There she would learn from a very experienced missionary wife, Abigail Beighton, about the problems of running schools for Malay and Chinese girls.

Thomas and Abigail Beighton had been assigned, with John and Joanna Ince*, to the newly created mission at Penang in late 1819. The two wives started a girls’ boarding school in 1820 and by 1821 it was flourishing – much to the chagrin of the LMS directors back in London. The directors felt it diverted attention from missionary work. But as the LMS didn’t recognise the wives as being missionaries there was little they could do! The boarding school was for fee paying students from wealthier homes and helped considerably to boost the meagre allowances the missionaries received. It was schools like these which encouraged the SPFEE to believe that their agents could be self-supporting.

Maria set up schools for Chinese and Malay girls in Penang and then in Melaka before the couple were re-assigned to Singapore. Many of the schools failed partly because the girls left after a few months as after puberty they were secluded in their homes until they were married. So the missionary wives devised a system for the Chinese schools which meant they were assured that girls would stay for a set period of time. Parents were asked to sign an agreement that their daughters would remain at a school for three, four or five years according to their age. The schools had to ensure that the girls were well protected.

When Maria moved back to Penang she sent her 10-year-old son, Samuel, to England but kept Burella (8) and Maria (6) with her. She received an allowance from the LMS and by late 1844 had 21 Chinese girls in a boarding school which was entirely supported by the sale of goods sent from England. It was in Penang that she met Johann Georg(e) Bausum who was born in Rodheim vor de Hohe near Frankfurt am Main in June 1812 and had worked on the Malaysian peninsular for about seven years. She was nine years older than him but had little doubt that they should marry. She wrote to the LMS:

“The Lord put it into the heart of a truly devoted missionary, Mr J G Bausum, to offer me his hand – and I think my usefulness will be greatly increased, my own spiritual benefit and that of my dear children, be greatly promoted. He has lived by faith, on the promises of God. And we believe that the Lord will do so still.” They were married in 1845 and settled in Penang where they took over the LMS work even though she gave up the mission allowance. She also continued with the girls’ school.

The Bausum’s, however, were married for just over a year when, on October 4, 1846, Maria died. Deeply bereaved George decided to send “my two darlings” (Maria’s daughters) home to England. He was allowed to continue using the LMS property and three years later he married Jemima.

John George Bausum wanted a wife who was as dedicated to mission work as he was – and he certainly found that in Jemima. And yet again she proved she was a survivor.

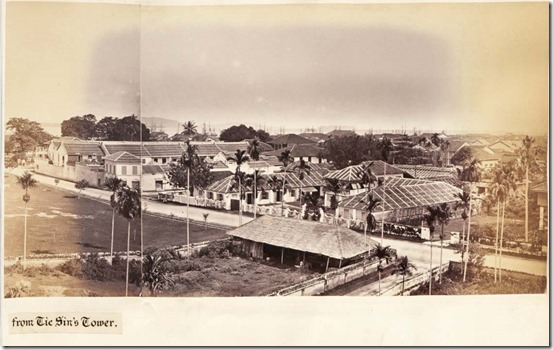

Below: Penang as Jemima would have known it. Photo taken between 1860 and 1900, now part of the Colonial Office photographic collection at The National Archives, available via Wikimedia Commons.

After their wedding in Singapore on May 23 1848 they returned to the LMS mission in Penang. The LMS gave approval for them to continue using the mission in exchange for taking care of the buildings, as had originally been agreed with John George and Maria. The buildings provided them with accommodation as well as space for the boys’ and girls’ schools. John George also bought an adjacent property so that the girls’ school could be extended.

Besides supervising two boys’ schools John George was very busy with his evangelistic and pastoral work which included training some young local men to help in the ministry. Meanwhile the Bausum family was growing: Mary Elizabeth was born in October 1849; George Frederick in November 1850; William Henry in January 1852; Samuel Gottlieb in July 1853; and Louisa May in March 1855.

The main problem for John George and Jemima was financing their work. As John George had gone out as an independent missionary he had looked for other ways of making a regular income and so had bought a plot of land on which to grow nutmegs and fruit. This, however, was not as productive as he had hoped. By early 1849 the girls’ school was failing to attract sufficient support and John George was considering joining a large mission. But he could not fully agree with the doctrines of the Church of England and the Free Church of Scotland decided to send its own minister. In 1852 he did receive public contributions towards the rebuilding of one of the boys’ schools but still went into debt.

There was worse to come. In April 1854 John George wrote in the family Bible: “Our dear Samuel Gottlieb departed this life on the 19th between the hours of 8 & 9 P.M. of the Malignant effluent small pox, which was conveid (sic) to him through the Vaccine matter the 30th of March, and which made their appearance on the 8th day after vaccination.” On March 1855 he had to record another death as little Louisa Jane survived for just six days after her birth. The doctor called it the “nine days disease” and stated that it was generally fatal.

Then, on August 1 1855, Jemima wrote: “My dear Husband departed this life after but one night’s fevering having sat up all the previous night with a dying member of his church.” He had collapsed on her shoulder. Shortly afterwards lawyer Jonas D Vaughan wrote to the LMS that John George suffered excruciating pain at the end and an autopsy had revealed that one of the principle arteries of his heart had ruptured.

Jemima then found herself in the midst of a financial nightmare. As it took so long to exchange letters between Penang and London there still had not been a satisfactory conclusion as to John George inheriting (via Maria) a building that Samuel Dyer had bought in Penang. If she could have sold that Jemima could have reduced some of the debt she had inherited. With John George dead some subscribers stopped giving funds but the Chinese Evangelisation Society (CES) continued to support two young local evangelists. Jemima had to give up one of the boys’ school but believed she could supervise that at the Penang mission along with the girls’ school and the church if the LMS agreed to the same leasing agreement as it had had with John George.

She wrote to the LMS in December 1855: “You could naturally ask what my plans are for the future – I can scarcely say that I have any at all, only my great desire is that this work should not be abandoned.” The hope of someone being sent to help with the work, along with the support of local Christian staff, kept her going. She was however suffering from enlarged tonsils which had meant that for three months she had been almost silent. There was little hope of recovery until her tonsils were removed, she said.

Her main concern was for her children. She explained that they were at the age when maternal teaching was most needed but she could bestow it upon them in very limited degree because she had to keep her power of speech for the school work. She felt trapped as she couldn’t fight or retire. She added: “But I do not forget that it is the Lord’s doing, and it is well.”

By July 1856 she gave up waiting for the Power of Attorney she needed from the LMS for the house Samuel Dyer bought. She told the LMS: “I am about to leave Penang for Ningbo for the sake of my children and being myself greatly in need of a change. I am and have been for the last month unable to speak above a whisper without much pain on account of swollen tonsils.”

She had managed to make sure their work would continue and had secured a teacher for the girls’ school. “I shall leave with many regrets but it seems the call of duty,” she wrote, adding that her agent would deal with the Power of Attorney. And she had won her battle to make sure their mission work would continue.

By 1859 both the girls’ and the boys’ school were under the auspices of the CES and there was a congregation of 20 local Christians at the church. The Society for Promoting Female Education in the East (SPFEE), which had obviously continued supporting the girls’ school after Jemima left, was informed that there were “18 Chinese, 10 Burmese, four Malays, three Arminians, one Siamese, one Kling, and one European” and that three of the students had been baptised that year. A local Christian woman was teaching embroidery and there was a Chinese Christian cook. Two older ladies kept discipline and one of the older girls was an excellent monitor. The school was supported by the sale of fancy goods which were sent by the SPFEE auxiliary committees in London, Geneva and Dublin.

The property that John George bought for an extension to the girls’ school meant that, when the LMS sold its mission buildings in 1870, some Brethren missionaries still had a base in Penang. Jemima’s heirs were delighted that a mission chapel was later built on that site and from that grew the Burmah Road Gospel Hall.

But why did Jemima go to Ningbo in China? The answer to that lay with the teenage daughters of Maria Dyer Bausum and an indomitable, very determined little woman called Mary Ann Aldersey.

(*Joanna Ince died in 1822 and in 1824 her husband was buried beside her and three of their infant children. The Beightons, however, carried on until Thomas died in 1844.)

Below: Map of Ningbo when Miss Aldersey had her school in the city. From A Woman Pioneer in China by E Aldersey White, The Livingstone Press, London, 1932.

Jemima, James Hudson Taylor and his Maria

By the time that Jemima reached Ningbo Miss Aldersey was a very influential member of the missionary community. Even the Chinese were in awe of her. Dr W A P Martin, an American Presbyterian who was in Ningbo from 1850 to 1860, wrote: “The most remarkable figure in the foreign community was Miss Aldersey, an English missionary. Born with beauty and fortune, she never married, not for want of opportunity, for she was known to refuse at least one offer. The (Chinese) firmly believed that as England was ruled by a woman, so Miss Aldersey had been delegated to be the ruler of our foreign community! The British consul, they said, always obeyed her commands.”

Miss Aldersey arrived Ningbo in 1843 and, with the assistance of three teenage girls, set up what was probably the first girls’ school in China. Like Sophia Cooke at the Chinese Girls’ School in Singapore she did not accept that only men (and ordained men at that) could be missionaries and so she too inspired Chinese girls and women to take part in mission work.

As an experienced matchmaker Mary Ann Aldersey realised there was nothing like a long trip into the azalea-carpeted hills that encircled Ningbo for a touch of romance. The only problem was that the young man was so out of breath trying to keep up with his beloved’s palanquin that he never managed to say “Will you marry me?”

By the early 1850s the foreigners could visit the hills around Ningbo and Miss Aldersey was quick to use a day-trip to bring two young people together. She took her matchmaking duties very seriously as she was responsible two very eligible foreign young women in Ningbo at that time: Burella and Maria Dyer. She had initially invited just Burella to help run her school. Burella, however, insisted that her sister, Maria, should accompany her. Miss Aldersey felt that as their work would be wholly among girls and they were sober minded and earnest their youthfulness would not be a bar to their both travelling to China. She said they were very missionary hearted and could largely support themselves.

When they arrived in Ningbo on January 12, 1853, Burella was 18-years-old and Maria was just four days short of her 16th birthday. They quickly settled in and soon became fluent in the local dialect as they had spent their childhood surrounded by Chinese. They were very much at home, whereas for another teenager Ningbo provided a hard and lonely start to an illustrious career in China1. Above: The type of river view which the Dyer sisters and Robert Hart would have seen on arrival in China after their long sea voyages. Drawing by C. F. Gordon-Cumming.

Robert Hart was 19-years-old when he arrived in Ningbo and was taken on a tour of the city by the British consul, John Meadows. A year earlier he was doing post graduate studies in modern languages and modern history at Queen’s College in Belfast when the British government was recruiting young men who could be sent to China to learn the language and become interpreters, especially as those already there had a knack of dying young. When he reached in Ningbo in September 1854 there were about 22 foreigners there. Most were missionaries (mainly American Presbyterians and Baptists plus a few from the British Church Missionary Society) along with some Roman Catholic priests, merchants, opium smugglers , consular officials and the occasional sea captain.

Having come from a family steeped in Wesleyan Methodism he attended church services and initially sought companionship among the missionary community. When he met Miss Aldersey he thought she was a very nice old lady but rather “old maidish in dress.” He was far more interested in the Dyer sisters and wrote about Maria: “I admire her so much that I can say no more about her.” He spent many pleasant evenings with the various missionary families and noted that the wives made superb cakes and jams. Hart became especially close to the Rev William Russell and his wife, Mary, who had been Miss Aldersey’s ward.

It was likely that it was at a Christmas dinner with a missionary family that Miss Aldersey noticed his longing to become acquainted with Maria. It was quite a feast: soup, leg of boiled mutton, two roast pheasants, a roast goose and a nice piece of bacon, followed by plum pudding, mince pies, tarts and blancmange. And afterwards he was able to sit beside Maria. “She is such a sweet nice girl,” he wrote in his diary.

So in April 1855 he was invited to join the Russells, Miss Aldersey, the Dyer sisters and some others on a visit to the hills. He wrote in his diary: “When going up the hill .. I walked by the side of Miss Maria D’s chair for about an hour, during which time I said very little & was near fainting half a dozen times, as I was about ‘declaring love’ & c. I once got so far as clearing my throat, but I lost my breath and could not go on. I let the opportunity slip – unfortunately or fortunately. I don’t know which! What a youth I am!” He never did get that special kiss he longed for. After that outing he seemed to have given up hope of winning Maria and also slowly moved away from the missionary community.

He was to prove far more flexible in his approach to the Chinese culture – a trait that would help him build bridges between the foreigners and the Chinese and so later be in a position to help China adjust to western modernisation.

He quickly realised that his salary would not enable him to support the sort of English wife who would expect to have many servants and was likely to be frequently ill. It was far cheaper and much less complicated to take a Chinese mistress and Meadows was only too happy to help him find one.

In July 1855 Hart gave up writing a diary for a few years and so provided no record of his view of the great unholy rumpus that tore apart the missionary community in Ningbo in 1857. Miss Aldersey, Maria Dyer, James Hudson Taylor and Jemima Poppy Bausum were at the centre of that row.

When Jemima arrived in Ningbo in October 1856 she and her children, Mary (7), George (almost 6) and William (4) were enveloped by a missionary community where everyone helped each other no matter what their denomination or background. It is likely she first went to Dr William Parker’s small hospital in a farmhouse among the paddy fields where her infected tonsils could be removed. By November she had moved to Miss Aldersey’s household in the city so that she could start learning how to run the school of 60 girls at which Maria and Burella Dyer and San Avong were teaching. Miss Aldersey was looking forward to retiring from the school she had founded in 1843 as she wanted to do more missionary work. The transition was hastened by the advent of the Second Opium War.

By the end of 1856 Guangzhou (Canton)had been seized by foreigners following a bombardment by British and French gunboats. Cantonese pirates around Ningbo were out for revenge and by January were planning to massacre all the foreigners. Several missionary wives and their children were evacuated to Shanghai and Miss Aldersey wanted to send the Dyer sisters as well. But when Jemima decided to move to the American Presbyterian compound across the river the sisters went with her (see map below). Miss Aldersey had agreed that when she retired her school would be amalgamated with that at the American Presbyterian compound and so the transfer was completed. But even if the Dyer sisters were no longer living with her Miss Aldersey believed she was still acting as their guardian while they were in Ningbo.

By late January she was concerned about Maria as the young woman had already turned down two proposals of marriage. That month Maria confided in the “wise and motherly” Jemima that she had been praying about Hudson Taylor after his first visit to Ningbo between October and December 1856. Then, in February, Maria believed those prayers had been answered for she received a proposal of marriage from him. Miss Aldersey, however, was adamant – Maria had to refuse him and tell him not to be in contact with her. Very soon even her sister, Burella, was telling Maria to stay away from Hudson Taylor.

For Maria it was going to be a long, hard year, one in which young Mary Bausum would remember her often looking very sad. “It seemed as if God’s will and Miss Aldersey’s were opposite,” Maria wrote to her brother, Samuel. It was hard to accept that a woman she had come to love and respect could be so wrong. As she struggled with this she wrote: “ … no man is infallible and I must allow no one’s judgement to come between me and my God.” 2

When Hudson Taylor returned to Ningbo in June 1857 he was very careful not to approach Maria. He soon found, however, that Miss Aldersey was actively working against him. She asked other missionary couples not to help the two to meet and told Maria not to visit those with whom Hudson Taylor was working. The missionary community was split, divided by Miss Aldersey’s fierce opposition to Hudson Taylor. He did find an ally in Jemima and it was from her that he learnt that Maria was interested in him. And it was Jemima who, in July, arranged a meeting between Maria and Hudson Taylor which she chaperoned. At that meeting Maria gave him permission to write to her official guardian in England, William Tarn, asking for permission to marry her. But it would take four months or more before he would get a reply.

Miss Aldersey was furious when she learnt that both Maria and Hudson Taylor had written to Tarn. To her Jemima was just as guilty because she had allowed them to meet. When Hudson Taylor went to see her she left him in no doubt how far she would go to stop him and Maria being together. She told him he was neither a Christian nor a gentleman because he had approached a minor without seeking her permission as Maria’s “guardian” in Ningbo. There was much more she had against him.

When he arrived in Ningbo in October 1856 he had already discarded the hot, tight fitting western apparel for Chinese clothing. In Shanghai he had been ridiculed by the foreign community for “demeaning their superior race” by dressing like a Chinese. He had done so because he did not want to be immediately recognised as a foreigner when he travelled illegally outside the treaty ports as an evangelist.

He was also often penniless because he was determined to “live by faith” and depend upon prayer to God for his daily needs. He wasn’t getting a regular allowance from the China Evangelisation Society as that agency didn’t have the funds to support the missionaries it had sent to China. But in addition his pietist beliefs led him to give to anyone who asked him for food and money. If that wasn’t enough he had broken the cardinal rule of travelling on a Sunday. He tried to explain to Miss Aldersey that he had been helping a missionary who needed urgent medical care when he had committed that “sin” but to no avail.

One of those who did understand him was Jemima for her late husband had wanted to “live by faith”. And, of course, Maria’s mother had also embraced John George Bausum’s pietist approach when she became his first wife. Maria’s father, Samuel Dyer, had given up studying for a degree in law when he felt the call to become a missionary – so it wasn’t much good telling her (as Burella’s fiancé, the Rev John Burdon did) that Hudson Taylor should go back to England and finish his medical studies before he could propose to her.

Miss Aldersey was not used to being opposed but in Maria, Hudson Taylor and Jemima she met her match. Maria was more in line with that strong independent streak of Protestantism which allowed each person to have their own personal relationship with Jesus and made it possible, even for a young single woman, to make decisions of her own so long as she felt they were backed up by God. As Hudson Taylor commented to his mother, the whole row centred on the fact that many did not think a maiden lady was qualified to judge on matters of love. He also wrote home about Miss Aldersey: “There is a good deal to be said in excuse for one now about 60, with failing memory, who has always ruled supreme over a large establishment and been spoiled by the deference and flattery shown her. She cannot brook contradiction.”

It was on December 11 that Maria received a letter from her aunt and uncle giving her permission to accept Hudson Taylor’s proposal so long as the wedding took place after her 21st birthday on January 16, 1858. The Tarn’s also asked Jemima to be like a mother to the young couple – which she was very happy to do. After that the young couple often met at her home where her daughter, Mary, noted that they flouted convention by sitting together and holding hands.

Miss Aldersey still tried to stop the marriage. Russell had sided with her in the row and so refused to officiate at the wedding even though he was the most senior CMS missionary in Ningbo. He also took the British Consul on a shooting trip on the day of the wedding -January 20. But the Consul signed the necessary papers before he went and left his deputy, Hart, to act for him.

On January 20 Hudson Taylor was penniless and his wedding suit was a plain cotton Chinese robe. Others rallied around to make it a special day and the Consul helped by returning the wedding fee in lieu of the groom’s assistance as a translator. The couple would go on to become two of the most influential missionaries in China in the 19th century through the mission they founded: the China Inland Mission. They would owe much to Jemima in the early days of that mission. But first Jemima had a price to pay for supporting the couple against the wishes of Miss Aldersey.

In the first few tough years of their marriage Maria and James Hudson Taylor would hardly have dared to believe they would be instrumental in founding one of the most influential Christian agencies in China – the China Inland Mission (now OMF International). That they survived and managed to develop a new missionary society was thanks to several special friends, including Jemima Bausum and the Rev Edward C Lord.

Maria and James Hudson Taylor were soon in need of Jemima Bausum’s hospitality. Not long after their marriage in January in 1858 they moved to a small cottage in a country town about nine miles from Ningbo. But both of them became very ill. They stayed first with some other China Evangelisation Society (CES) missionaries and then convalesced at Jemima’s home.

Afterwards they moved to an apartment above the room that the CES missionaries used as a chapel in Ningbo. It was then that they heard that Jemima would be replaced by some American Presbyterian missionaries at the school. Hudson Taylor wrote: “I should be sorry for her to have to return to England from want of support. Perhaps some aid might be got here, but unless nearly £40 a quarter could be raised at home, I fear she and her family and the mission work could not be sustained.”

He told his mother later: “She is a zealous, useful missionary and her influence has been greatly blessed on those who were under her care. You know how kind she was to me, and that too when others were afraid to aid me, however much they felt with me. And I may add that her loosing (sic) her position in the school was probably owing in part to her kindness to me.”

By July 1858 he was able to report that Mary Ann Aldersey and the Russells were more friendly if not familiar towards him, and that Burella had started writing to her sister, Maria, again. Little did they realise that they had just one more month to enjoy this renewed relationship with Burella – for the latter died of cholera in Shanghai in August.

It is likely that they received that news after Jemima had left Ningbo. In a letter to his mother on September 16 Hudson Taylor wrote: “Mrs Bausum and three children are now on their way to England nearly six weeks. She has taken my part in the difficulties I have had and since we have married I have staid (sic) in her house some time. She has promised to come and see you while in England & I am sure you will be pleased with her, and her kindness to me will be a claim on your love. I hope she will come out again ere long.”

He sent a letter of introduction with Jemima to the Tottenham Ladies’ Association, a Christian group which was supporting him. And in England Jemima and her children went to live with Maria’s uncle, William Tarn, and his wife. She needed all the help she could get because, with the loss of her position as headmistress of the school in Ningbo, she was left homeless and almost penniless.

Jemima was kept busy in England getting her children settled and trying to raise sufficient funds so that she could return to Ningbo and open her own school. She successfully applied for a grant from the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East ( SPFEE) and made many friends, particularly in Tottenham, among those who believed in “living by faith”.

Her own husband, John George Bausum, had been inspired by the teachings of Anthony Norris Groves (1795-1853), as had George Muller, the founder of the orphanages at Ashley Down in Bristol. Through prayer and by only accepting unsolicited gifts Muller saw thousands of children cared for in those orphanages. He even received sufficient funds to support some missionaries including Hudson Taylor.

By July 1859 the Hudson Taylors were looking forward to Jemima’s return and had sent a list of books for her to bring as well as a compound microscope and other items.

(Jemima left her daughter, Mary, and two sons in England. Mary moved in with the Hudson Taylors when they were in England and became like a member of their growing family. But George and William did not settle so well. )

By the time Jemima got back to China much of that country was under the control of the Taiping rebels, led by a man who believed he was the younger brother of Jesus. The Chinese emperor had failed to ratify the Treaties of Tientsin and this led, in October, to Lord Elgin with the French General de Mountauban ordering the destruction of the magnificent imperial Summer Palace in Peking. Beset by the Taiping rebels and the foreigners, the Chinese had to submit to the Allies’ demands. The Peking Convention signed in 1860 treaty even allowed for the British to appoint the head of the Imperial Maritime Customs.

The missionaries were pleased to hear that they would have more freedom to travel inland but were appalled at the enforced legalisation of the opium trade. After the Peking Convention the opium dens grew faster than schools in China. Not surprisingly the Chinese deeply resented such “unequal treaties” not just for the imposition of the opium trade but because foreigners often enjoyed more privileges than they did.

By early 1860 Jemima had 11 girls mainly under 10-years of age in her school. She told the SPFEE: “They had been sadly neglected, never comfortably clothed or fed, and looked much such a picture of starvation and misery as we are familiar with in our ragged schools at home. One poor child was brought to the house, and the message left that the teacher might do what she liked with her. Then three are afflicted – one with total and two with partial blindness, while a fourth was a cripple. But they are not wanting in intelligence, and a few months after their admission, five out of the eleven had learnt to read Chinese as it is spoken in Ningbo. Their time was very pleasantly spent – very different to their former days of wretchedness. They learned to be useful children, to cook their own rice, make their clothes, and clean their rooms.”

The circle of friends around Jemima and the Hudson Taylors included an American Baptist Union missionary, the Rev Edward C Lord. Lord had gone to Ningbo in 1847 with his first wife, Lucy Lyon who was a niece of Mary Lyon, the pioneer of women’s education in the States and founder of Mount Holyoke College. Lucy gave birth to two children but both died in infancy and then, in 1852, she became ill. Her husband took her to back to Fredonia in New York State where she died in May 1853 of “intestinal tuberculosis”. In November that year he married her younger sister, Freelove, and they went to Ningbo together. Lord was bereaved yet again in early 1860 when Freelove died soon after their fifth child was born.

In December 1861 he married Jemima. Hudson Taylor had worked with Lord and obviously highly respected him. He asked Lord to oversee and help the young missionaries who had been sent out by the CES (John and Mary Jones and James and Martha Meadows) while he and Maria were in England. The Hudson Taylors left Ningbo in late 1860 and did not return until 1866 – after the China Inland Mission had been founded.

As Jemima had not signed a marriage pledge with the SPFEE she did not have to return any of the society’s grant. That was fortunate because her vision was to build an even bigger and better orphanage and school. These plans soon had to be put on hold because the Taiping rebels were heading towards Ningbo. By mid 1861 thousands of Chinese were fleeing to Ningbo as the Taiping rebels attacked nearby towns and Dr Parker’s new hospital was over-flowing with casualties.

Jemima decided to close the school in the city and send the girls to a safe place across the river. She ventured forth from the American Baptist compound in September to visit the Joneses as John was very ill. On the way back she found the canals full of boats overflowing with refugees. Streams of fearful people were passing the Lord’s home sharing stories of how the rebels had slaughtered so many and burnt their houses.

The panic was palpable but Jemima commented: “I do not indulge in fear.” At a Bible class she managed to keep the attention of the few Chinese women there by discussing “Fear not them that kill the body…” For the next two months there were so many terrifying rumours about what the rebels would do.

The circle of friends around Jemima and the Hudson Taylors included an American Baptist Union missionary, the Rev Edward C Lord. Lord had gone to Ningbo in 1847 with his first wife, Lucy Lyon who was a niece of Mary Lyon, the pioneer of women’s education in the States and founder of Mount Holyoke College. Lucy gave birth to two children but both died in infancy and then, in 1852, she became ill. Her husband took her to back to Fredonia in New York State where she died in May 1853 of “intestinal tuberculosis”. In November that year he married her younger sister, Freelove, and they went to Ningbo together. Lord was bereaved yet again in early 1860 when Freelove died soon after their fifth child was born.

In December 1861 he married Jemima. Hudson Taylor had worked with Lord and obviously highly respected him. He asked Lord to oversee and help the young missionaries who had been sent out by the CES (John and Mary Jones and James and Martha Meadows) while he and Maria were in England. The Hudson Taylors left Ningbo in late 1860 and did not return until 1866 – after the China Inland Mission had been founded.

As Jemima had not signed a marriage pledge with the SPFEE she did not have to return any of the society’s grant. That was fortunate because her vision was to build an even bigger and better orphanage and school. These plans soon had to be put on hold because the Taiping rebels were heading towards Ningbo. By mid 1861 thousands of Chinese were fleeing to Ningbo as the Taiping rebels attacked nearby towns and Dr Parker’s new hospital was over-flowing with casualties.

Jemima decided to close the school in the city and send the girls to a safe place across the river. She ventured forth from the American Baptist compound in September to visit the Joneses as John was very ill. On the way back she found the canals full of boats overflowing with refugees. Streams of fearful people were passing the Lord’s home sharing stories of how the rebels had slaughtered so many and burnt their houses.

The panic was palpable but Jemima commented: “I do not indulge in fear.” At a Bible class she managed to keep the attention of the few Chinese women there by discussing “Fear not them that kill the body…” For the next two months there were so many terrifying rumours about what the rebels would do.

Then, in December 1861 Jemima wrote to the SPFEE: “The rebels have entered and sacked the city to a house, and laid waste all the surrounding country. No pen, much less mine, can describe the ten-thousandth part of the wretchedness to which our eyes and ears are witness. All trade is stopped, and vast numbers look forward to nothing but starvation and death, even should they escape the rebels’ knife. Many are robbed of all they have while seeking a place of safety. The people are distressed beyond description. Might is right.”

The missionaries were not attacked by the rebels but Jemima had the agony of turning away many orphans because she did not have the funds to take care of them. The only foreign woman who stayed in the city was Mrs Mary Leisk Russell. She and her husband, the Rev William Russell, provided a refuge for about 200 Chinese and fed the destitute. Mrs Russell was known as a timid woman but still successfully stood up to the rebels when they tried to carry off some of her school girls.

The rebels were besieged by Chinese Imperial forces in May 1862 and made the mistake of firing upon French and British ships. The ships fired back and so helped the Imperial army to force the rebels to leave Ningbo. The British had already decided to help the Imperial army to defeat the rebels and by 1864 that was fully accomplished, one of the heroes being “General” Charles Gordon who would later be killed at Khartoum in Sudan.

In April 1863 the Lords decided that Jemima should take her husband’s five children (Lucy Lyon, William Dean, Franklin Lyon, Fannie Adaline and Mary Freelove) to his sister in New York State. It would be more than a year before she returned to her husband and her work.

Jemima and Edward Lord’s five children were on the steamer from Shanghai to New York, via Cape Horn, for three months – but it was obviously well worth it for she was so impressed by her sister in law, Esther Lord McNeil and the educational facilities around the McNeil’s home in New York State.

Aunt Esther and her husband, James, were dedicated temperance workers and she became the first county president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in New York State when it was formed in 1873. It was about a month after she married in 1832 that she became a Christian and felt called to care for homeless children. The McNeils never had any children themselves but by the mid 1860s they were caring for eight youngsters. These included Edward and Freelove Lord’s five children (Lucy, William, Franklin, Fannie and Mary) and George and William Bausum. For in 1863 Jemima had decided to go to England collect her boys and take them to live with Aunt Esther. George (below left) was then 13-years-old and William was 11.

In England Jemima spent time with her daughter, Mary, who was very much part of the Hudson Taylor family. She did manage to raise some support for her work in Ningbo while there particularly through George Muller (founder of the orphanages at Ashley Down in Bristol) but fund raising in the States proved to be very difficult because of the Civil War. Nor did it help that, when she was in Brooklyn preparing to return to Ningbo, she caught diphtheria. Jemima didn’t get back to her husband until July 1864 having spent most of the last 14 months at sea.

Dr Lord had been very busy during her absence both with his own work, overseeing the construction of the orphanage, helping those missionaries (like James Meadows) who looked to Hudson Taylor for leadership and acting as vice-consul during the American consul’s absence. He would also survive what was thought to be cholera and, when scarcely off his sick bed, baptised 15 converts, 11 of those at the Bridge Street church that he was overseeing for Hudson Taylor. Once back in Ningbo Jemima was soon immersed in more than just her school work.

As the orphanage approached completion she felt frustrated that she could not do more evangelism among the women in and around Ningbo. She began systematically visiting nearby villages with a local Christian worker, Mrs Tsui – known as the “man hunter” for the way she sought to introduce many Chinese to Jesus. Jemima told the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East and Hudson Taylor that the two Biblewomen she worked with had such easy access to so many homes in Ningbo that she didn’t know how to cope with all the work.

She wrote that if she had five helpers she could easily give each one a district in which there was ample employment – leaving her free to teach women to read the Scriptures in Romanised colloquial script. Hudson Taylor and his associates in London did recruit an assistant for her but that young woman never settled into the work at the school and soon left. He described Jemima as being the equivalent of one good man!

By 1865 Dr Lord felt that Meadows, after three years in Ningbo, was ready to take responsibility for the Bridge Street church which by then had about 40 members. He was, however, even more impressed by another of Hudson Taylor’s recruits – Stephen Barchetwho had arrived in July 1865. Barchet was German and had been converted in London when he was studying medicine. Dr Lord described Barchet as a young man of unusual promise who was more intelligent and more teachable.

Hudson Taylor sent others to Ningbo, including a couple who stayed at Jemima’s school for a while. But the Lords and Meadows were very keen to see the Hudson Taylors return. Maria had, however, been very ill after the birth of her third son, and there was still much to do before they could leave England. They were seeing the impact of the Christian Revival in Europe and by 1865, after they founded the China Inland Mission, they had many applicants to assess. As their plans progressed for a whole team to travel with them to China in 1866 Dr Lord encouraged them by stating that they could all find a home with him and his wife when they first arrived.

That team of 16 new workers included Jemima’s 16-year-old daughter, Mary, whom Hudson Taylor accepted as a missionary. He well knew how effective his own wife had been in Ningbo even though she had also been only 16 when she first went to China. This team would pioneer the inclusion of single women and non-ordained men in Christian outreach deep into China.

The Hudson Taylors with their four children and that team left England in May 1866 on the Clipper Lammermuir and arrived in Shanghai on September 30. Hudson Taylor immediately escorted Mary Bausum and Elizabeth Rose to Ningbo, for the latter was engaged to Meadows. He didn’t take the Lords up on their offer of hospitality for the team – but did continue to cherish their encouragement and support.

Barchet left Hudson Taylor’s team and joined Dr Lord in his work in Ningbo while Mary became her mother’s assistant. It didn’t take long for romance to blossom between Barchet and Mary and they married in November 1868. Sadly Jemima never witnessed the birth of her first grandchild for she died on January 15,1869.

A doctor reported that her health had been declining during the past year but she had continued to do her work till the last week or two of her life. His diagnosis was that she had pleurisy “which ended in effusion of water on the chest”. This was summarised by her daughter and son-in-law as probably being heart disease and bronchitis.

They wrote: “Her sufferings during her final illness were great, not being able to lie down nor get rest. But her faith remained unshaken, and her mind seemed to be quite calm.”

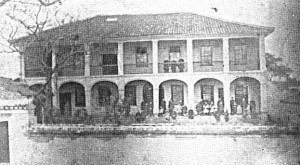

Above: Jemima’s school in Ningbo. Below:Mary Bausum Barchet in about 1925

Her daughter added: “Mamma is very much missed, not only in the family circle, but also by the Chinese, who say she is the ‘only lady who mingled so much with them, and worked so hard for them.”

Her husband wrote: “She had labored long and well; it was right she should go home to her rest. For seven weeks she bore her severe sufferings with great fortitude and patience, and closed her great battle of life.” He spoke of how dauntlessly, tirelessly and hopefully she had worked – and his sorrow at losing her.

Jemima told one of the Biblewomen shortly before her death that she was very well as she was going to her Father’s house and so looked forward to death.

In an obituary about her a newspaper in Fredonia (where the McNeils were living with her children) it stated that her school, with almost 50 girls, was the largest and most successful in China. It still exists today but looks very different now that it has been completely rebuilt and modernised.

There would be more sorrow the year after Jemima’s death, as Maria Hudson Taylor died after giving birth to her eighth child (that son and th ree other children pre-deceased her). ToMary Bausum Barchet she had been like a very special big sister.

Mary carried on her mother’s work at the school and the orphanage for a while. In the 1870s the Barchets went to the States where Stephen completed his medical studies and they joined the American Baptist Missionary Union. They returned to China and worked there for the rest of their lives. They had four daughters and one son.

Dr Lord would marry three more times. In 1887, 40 years after he first arrived in Ningbo, he and his sixth wife contracted cholera. He was so ill that he never knew that his wife had died – four days before he did. So he and five of his wives were buried in Ningbo.

The Bausum boys made their lives in the frontier lands of South Dakota. In August 1885 William married Dr Lord’s daughter, Fannie Adaline, but then had to leave immediately for South Dakota where his brother, George had died suddenly. He brought back George’s son to Aunt Esther.

William and Fannie (who had acted as secretary to her father in Ningbo for several years) then went to South Dakota themselves. They had seven children one of whom, Robert Lord Bausum, enjoyed telling his children that his mother’s father married his father’s mother (He Led All The Way pp 20 &36). He was with the Southern Baptist Foreign Mission Board in China in 1929 when he married Euva Evelyn Majors and their fourth child, Dorothy (Dorothy Lord Bausum Evans), carried on the family tradition of missionary service. When Dorothy and her husband, Bobby Dale Evans, retired from the mission field in 2000 it was Joy Bausum who picked up that torch.

Sources : I am very grateful to Dan Bausum and Dorothy Evans (Jemima’s great grand daughter) and to Margaret Troy for sharing information about Jemima. * In the family Bible of John George and Jemima Bausum there is a note that Jemima was born in Great Yarmouth, England, on February 17, 1818.

The records of the SPFEE in the special collection at Birmingham University; the History of the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East published in London in1847 by Edward Suter; and The Female Intelligencer published by the SPFEE.

Mission to Borneo – The Historical Society of the Reformed Church in America Occasional Papers No 1, by Gerald de Jong, 1987; Queen of the Head Hunters by Sylvia Brooke, Sedgwick & Jackson, 1970.

Incoming letters to the London Missionary Society, in the Archives of the Council for World Mission, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Christine Doran, A Fine Sphere for Female Usefulness, Missionary Women in the Straits Settlements, 1815-1845, Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic society Vol LXIX pt 1 1996.

E Aldersey White A Woman Pioneer in China, The Life of Mary Ann Aldersey, The Livingstone Press, London, 1932.

A Brief History of Noncomformist Protestantism in Penang and the Mission House at 35 Farquhar Street, Submission to The Penang Story, Volume 2, by Jean DeBernardi.

Dorothy Lord Bausum Evans He Led all the Way, Xulon Press 2007 – I am especially grateful to Mrs Evans for sharing the information in the Bausum’s family Bible.

See also http://www.penang-traveltips.com/farquhar-street-mission-house-and-chapel.htm

Katherine F Bruner, John K Fairbank and Richard J Smith (Eds and narratives) Entering China’s Service – Robert Hart’s Journals 1854-1863, Harvard University Press 1986, pp 8-9, 62-63, 70,71, 84, 96-97, 128-129.

Church Missionary Society Intelligencer 1853 (Report of the Bishop of Victoria about a visit to Ningbo in the spring of 1852).

About Maria Dyer and James Hudson Taylor : J C Pollock Hudson Taylor and Maria, Hodder & Stoughton 1962, pp 81-105; Geraldine Guinness The Story of the China Inland Mission,Morgan and Scott 1894; and A J Broomhall If I had a Thousand Lives – Hudson Taylor & China’s Open Century Vol III Hodder & Stoughton 1982.

The Ricci Roundtable, website of the Ricci Institute

The Project Gutenberg eBook: Frances W Graham and Georgeanna M Cardenier, Two Decades – A History of the First Twenty Years’ Work of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union of the State of New York, 1894. The photograph of Esther Lord McNeil is from that book.

1. From 1863 to 1908 Sir Robert Hart was the Inspector General of China’s Imperial Maritime Custom Service.

2. Maria Dyer’s letter to her brother, Samuel, in July 1857, China Inland Mission archives in the special collection at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

See also: A Charter for Girls’ Education and Eliza Thornton – a singular success

I am especially grateful to OMF International and to the staff at the special collection at SOAS for the chance to access some of the letters of James Hudson Taylor. This made it possible to be certain exactly when Jemima left Ningbo in the late 1850s, and again in the early 1860s. The letters of E C Lord are in the CIM archives in the special collection at SOAS.

My thanks to Dan Bausum, Joy Bausum’s father, for providing copies of photographs from the Bausum family archives.

Dates:

Jemima Bausum Lord 1818-1869; Edward Clemens Lord 1817-1887; Mary Elizabeth Bausum Lord 1849 – 1926; Stephen Paul Barchet 1843 – 1909; George Frederick Bausum 1850 – 1885; William Henry Bausum 1852 – 1905; Fannie Adaline Lord Bausum 1858 – 1927; James Hudson Taylor 1832 – 1905; Maria Dyer Taylor 1837 – 1870; Robert Lord Bausum 1893 – 1979; Euva E Bausum 1900 – 1966.

Comments:

From Dan Bausum, December 1, 2010: I am enjoying your story very much. I look forward to each installment. Patty and I retured recently from Malaysia where we attended the dedication of the Joy Bausum School. There were dignitaries there, who, based on their education and accomplishments were highly esteemed by men and there were refugee children, many of them orphans sitting with them. I was struck by the contrast and the fact that Jesus was equally comfortable with either group. So was Joy. It brought us inexpressable joy. We did get to visit Penang and found the grave of John George Bausum, Jemima’s first husband and the mission house that was built on the property he and Jemima bought next to the girls’ school. I appreciate you sharing your research in the form of this story. Dan Bausum

From Beth Feb 22, 2014: I too am enjoying this story of my great lineage. These are some very strong and courageous women of whom I get my DNA. This helps me understand where I get my boldness to serve my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. I am the great great great granddaughter of Jemmima as well. My G G Grandparents were Mary and Stephen Barchet. I understand there is a hospital in his name? This was so wonderful to read about my great great great grandmother Jemima and her daughter Mary and husband Stephen, which (of course) I am related to as well. Wonderful to know these good kind Christians are part of my DNA~~~smile!

From Doc M August 19, 2011: Interesting post! I am a great-great-great-grand-daughter of Jemima’s older half-sister Mary Poppy and her husband Stephen Todd.